Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660)

Get a Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) Certificate of Authenticity for your painting (COA) for your Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) drawing.

For all your Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) artworks you need a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) in order to sell, to insure or to donate for a tax deduction.

Getting a Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) Certificate of Authenticity (COA) is easy. Just send us photos and dimensions and tell us what you know about the origin or history of your Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) painting or drawing.

If you want to sell your Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) painting or drawing use our selling services. We offer Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) selling help, selling advice, private treaty sales and full brokerage.

We have been authenticating Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) and issuing certificates of authenticity since 2002. We are recognized Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) experts and Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) certified appraisers. We issue COAs and appraisals for all Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) artworks.

Our Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) paintings and drawings authentications are accepted and respected worldwide.

Each COA is backed by in-depth research and analysis authentication reports.

The Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) certificates of authenticity we issue are based on solid, reliable and fully referenced art investigations, authentication research, analytical work and forensic studies.

We are available to examine your Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) painting or drawing anywhere in the world.

You will generally receive your certificates of authenticity and authentication report within two weeks. Some complicated cases with difficult to research Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) paintings or drawings take longer.

Our clients include Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) collectors, investors, tax authorities, insurance adjusters, appraisers, valuers, auctioneers, Federal agencies and many law firms.

We perform Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez art authentication, appraisal, certificates of authenticity (COA), analysis, research, scientific tests, full art authentications. We will help you sell your Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez or we will sell it for you.

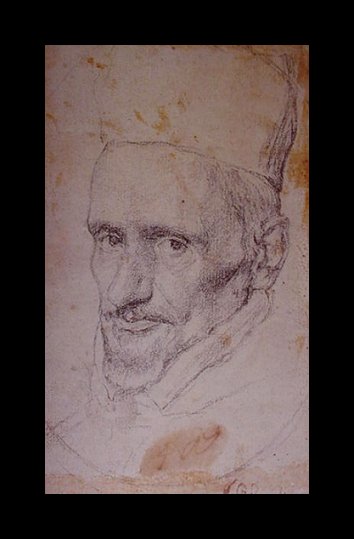

Velázquez was born in Seville in 1599 and died in Madrid in 1660. His paintings epitomize the art of painting at its very best. In his early days Velázquez would draw on blue paper with charcoal and white chalk. The subjects were simple. One should not expect great returns on these, as opposed to his later works in oil.

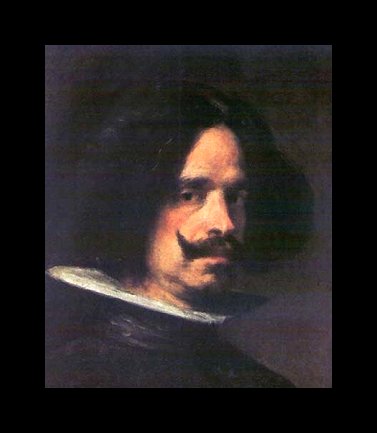

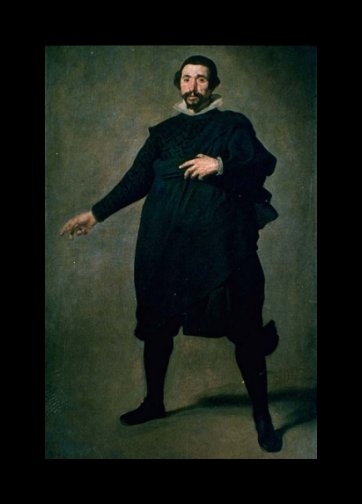

His main body of work consisted of portraits, genre scenes and paintings of mythological sitters.

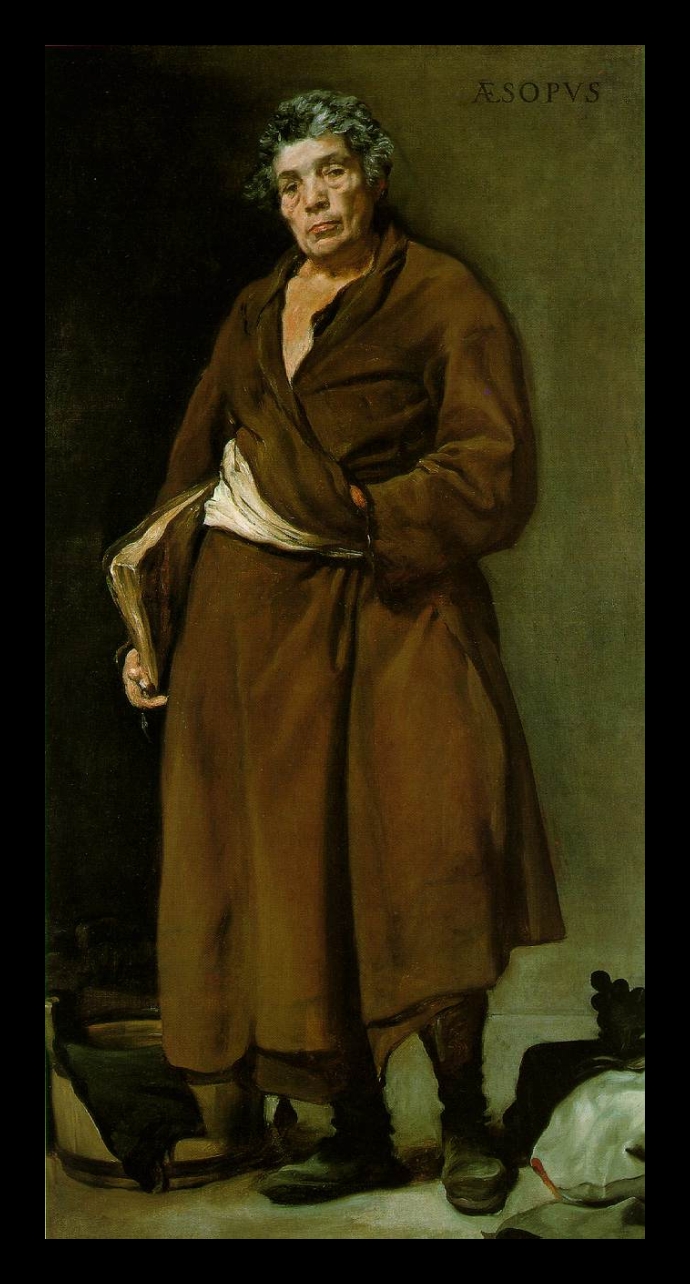

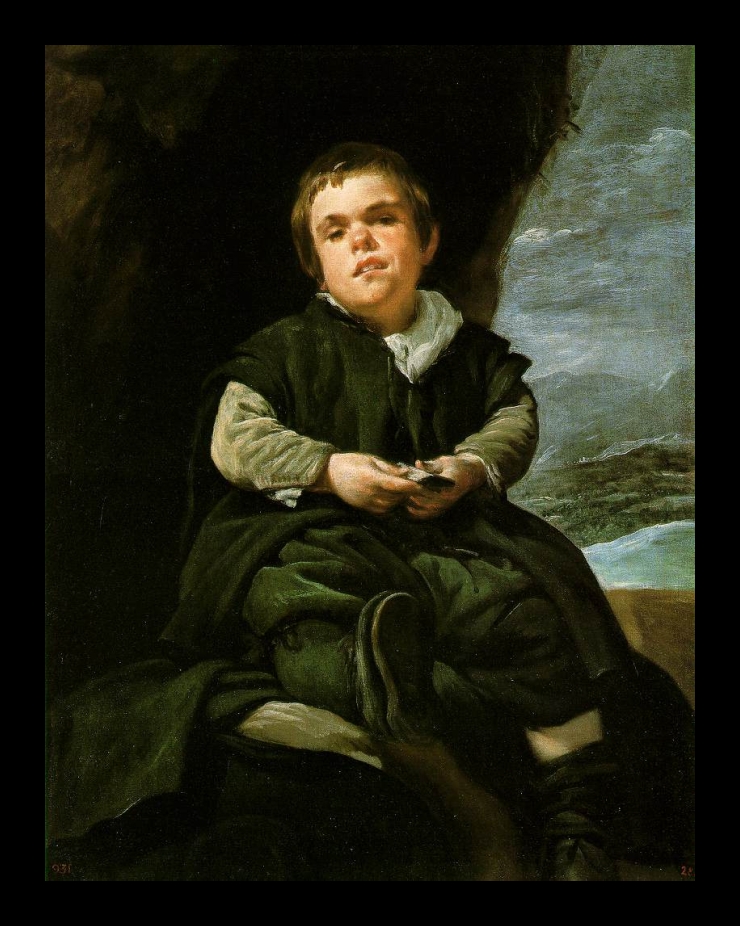

In particular, Velazquez seemed to have a fascination with dwarves and incorporated them into his scenes, and also painted their portraits.

When he visited Italy, one stay lasted a year and a half and the other about two years, he drew for many weeks the works of Michelangelo, Raphael and probably of other great Italian masters. We know that he met with Caravaggio and Titian and was extremely impressed with the work of the latter. He also sketched antique sculptures. All of these drawings are missing.

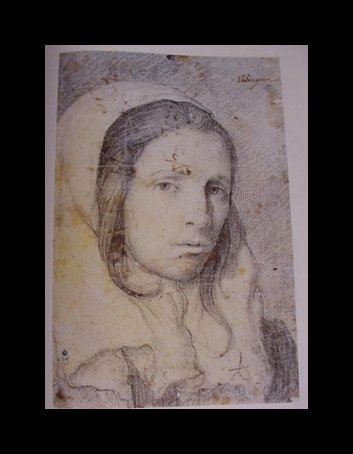

Of his approximately 130 works currently known, only five are drawings, two of them being on the recto and verso of the same leaf, meaning that we only have four sheets of paper from Velázquez. This is a surprisingly small number because in most instances an artist leaved far more sketches and drawings than oil paintings. For nearly 40 years he was the appointed painter at the Spanish court. He had a workshop in the palace and assistants. This was an active operation, but all we have are the five sketches shown below. All others have vanished.

It is worth noting that none of the 5 sketches represent any part of any known painting by Velázquez. The drawings on the recto and verso of the same sheet probably show studies for the Surrender of Breda but they do not represent anyone actually in the painting. As for the drawing of Cardinal Borja, we have an account that Velázquez painted his portrait, but the painting is lost. So we do not know if the drawing matches the painting. Velázquez probably produced 30,000 drawings and we have five. It is an absurd situation.

Compare this to Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo died 140 years before Velázquez, but we have 5,000 pages of his notes (mostly gibberish). Or take Rembrandt, who lived at exactly the same time as Velázquez, and died just 9 years later. There are 2,000 known Rembrandt drawings in existence today. So, what happened to the other 29,995 drawings by Velázquez? They all burnt? They were all eaten by mice? It seems impossible that almost every last sketch he ever did would have been destroyed.

One possibility is that a stack of his drawings, perhaps a packet comprising a few hundred of them, is somewhere in the dark cellars of a museum. The usual suspects are of course the large old museums of Spain, France, Italy and Russia, because they all have thousands of crates and boxes nobody has ever opened.

One museum in Italy estimates that it has 30,000 old master drawings nobody has ever sorted, catalogued or looked at. Well, actually, yes, someone started looking at some of them; it was back in the 1700s according to the records, so these statistics may not be exactly accurate.

The Prado in Madrid is in some ways, a treasure trove for masterworks. Apparently, their inventory isn’t completely catalogued, and according to history, has never really been. Unfortunately, because of this they lose paintings and are not sure what they have. History has also shown that this kind of storage is not good for art, and sadly, some great pieces have been lost. Paintings and drawings are stored wherever, at random, with no tags or identification, like the one they found in the attic recently:

“MADRID, Spain (AP) — Renovation workers have stumbled upon a previously unknown painting by the 18th-century Spanish master Francisco de Goya.

The Prado Museum confirmed Friday that the canvas was found 10 days ago propped against a wall in the attic and was indeed a Goya.

“From the moment we saw it, it was marvelous,” said Carmen Garrido, one of several Prado curators who examined the colorful 8 x 6 foot work, apparently intended to hang behind a church altar.

“It is an exceptional work for its quality and complexity of execution,” Garrido said.

Nobody knows how a Goya ended up stacked in the attic.

“How long has it been here? A long, long time.”

Garrido said the museum had no record of the painting. On the back of the canvas is an inscription ordering it to be restored in 1865.”

Velazquez signed few of his paintings and probably none of his drawings. The names on the few sketches we have were added later.

Many of his paintings have perished by fire and acts of war, so that in many instances one cannot easily relate a sketch to a particular painting.

So, while it is a near certainty that there must be some Velazquez drawings out there, it will take very discerning eyes and a bold intuition to see the Spanish master’s hand in them.

DISCOVERY OF A VELAZQUEZ PAINTING

A painting, long thought to have been by the 17th-century Spanish artist Murillo, has been re-attributed to Velazquez, after X-rays revealed distinctive palette-knife markings.

Studies of Saint Rufina also uncovered stylistic links to Velazquez’s Sybil in the Prado, Madrid.

The painting was first recorded in the inventory of Don Luis de Haro. In 1643 he had succeeded his uncle as Prime Minister to King Philip IV of Spain, whose favorite court painter was Velazquez.

The painting disappeared until 1868, when it resurfaced in the collection of the Earl of Dudley as the work of Bartolome Esteban Murillo. In 1925 the 3rd earl sold the painting and in 1948 it came up for sale in New York when it was bought by the family of the present owner. It had remained unseen by the public ever since.

In 1963 Lopez-Rey first referred to a lost Velazquez of Saint Rufina. A thorough technical examination of the painting confirmed the attribution and established a date for the work between 1632 and 1634.

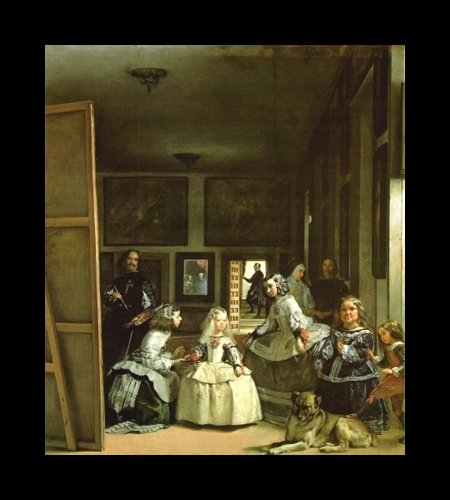

ABOUT LAS MENINAS

Of late, this painting has been the subject of countless interpretations and essays. Here is what we think of it.

Velazquez was not just an extremely talented man as a painter, he was also a glutton for honors, titles, position, power and prestige.

The most remarkable thing about his life, next to being one of the world’s greatest painters, is that he managed to remain the pet of the king of Spain for nearly 40 years.

He received promotion after promotion, and never had enough. He managed to get the king to intercede for him, so that the rules of admission in the Order of Santiago would be modified, and he could become a Knight.

He went far beyond being a court painter, and then the king’s painter. He was superintendent of building projects and also chief chamberlain of the royal household. He supervised the preparation of the most important state events, such as the visit of the king of France for his wedding to the king of Spain’s daughter.

When he went to Italy, it was with letters of recommendation from the king to the Pope, and to the most important rulers in Italy. He was treated everywhere he went as royalty himself, as a representative of the king and an intimate friend of the monarch.

Interestingly, when he returned from Italy he was now carrying letters of recommendation from the Pope, again to be admitted in some of the aristocratic orders he so badly wanted to join. This goes to show how very ambitious he was and obsessed with his advancement. A visit to the pope is turned into asking the pontiff for help and support of his personal ambitions.

Velazquez reached and remained at the very top of the social pyramid and it took much more than being a great painter to get there.

It took an uncanny ability, to survive and to thrive for 40 years, in the reptilian pit of court intrigue.

It also took enormous ambition and a gigantic ego and Velazquez had both.

Las Meninas is nothing but a self-serving portrait Velazquez designed to give himself greater prominence, and more importance, than even the king and queen of Spain had.

The device he used was to portray himself at work in front of a gigantic canvas and then to pepper royalty all around himself.

One can hardly object to his depicting himself painting, it seems so humble, but the canvas is so imposing that it is the most visible item in the painting.

Right there, with this canvas in our face and Velazquez standing in front of it, we realize that this is the central subject of the painting.

He wanted and needed the king in the picture, to show the world that he lived at the epicenter of royalty and power, in constant and direct contact with the monarch.

But he also wanted in this ultimate ego painting to be seen as more prominent. Royalty surrounding him and admiring him, as opposed to the opposite.

So the trick he thought of was to show the king and queen reflected in a tiny mirror, as if they were no bigger than little dolls.

Toys in the hands of the great Velazquez.

The canvas is prominent, Velazquez is prominent, but the king and queen have been reduced to nothing, even though they are there, respectfully admiring Velazquez from a distance.

This was good, but not enough. Something else was needed to hide the fact that the whole composition is about Velazquez.

Brilliantly, he introduced the little princess and her retinue of young court ladies and dwarves. All lesser than him by virtue of their young age or short stature. This would do the trick. He would be able to pass on the painting as some unusual portrait of the princess.

As a final trick, he placed a large dog prominently in front of the royal kid. It takes the focus away from the princess. The large dog fights for attention whenever one looks at the girl. It is also for Velazquez a way of saying that the dog is as important as the princess, or that she is no more prominent than a dog.

The painting is a monument to Velazquez.

It means “Look at me Velazquez, I have achieved more than anyone. Even the king and queen admire me from a respectful distance. I am the architect of this entire scene and it is all about me. I stand prominently in its center and dominate all”.

If there would be a doubt about this interpretation, consider the paintings Velazquez depicted on the wall. One is Pallas and Arachne, the story of an artist challenging the goddess Athena. The other painting shows another artist again challenging a god; Apollo and Marsyas.

Why would Velazquez, of all paintings, have chosen these two for the background of his own creation?

Simply to make his message eloquently clear, to those who understand these things, that Las Meninas is really about him Velazquez, challenging the superiority of the king.

We research, authenticate and appraise paintings and drawings by Velazquez, from his workshop, by his assistants, by his followers, and by the other Spanish painters of his day.

Still wondering about a painting in your family collection? Contact us…it could be by Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez.